Granny has been reflecting on the connection between habit and ritual, whether they are ever one and the same. A habit of course - even a long established one - is not exactly a ritual in a religious or social sense the way a mass is on the one hand, a yearly Carnival procession on the other. (Carnival, religious in origin, of course, is largely social these days, trailing on through what should be the austerity of Lent.) Yet a habit established over the years, whether a daily one - like cleaning your teeth at a particular time in a particular way- or an annual one like marmalade making or the grape harvest that defines the turning of the year- does become a ritual in a way. It certainly becomes so for the old. Maybe it is part of the way they are able to connect to the past, so hang on to an ever shifting unfamiliar present. (Granny is trying to prevent herself going too far down

this road. She does not, for instance, still, have any rules about what time of day she does anything. Though she will admit that over recent years the past - memory of it - has become a more significant component of her present. One reason probably she is writing this.)

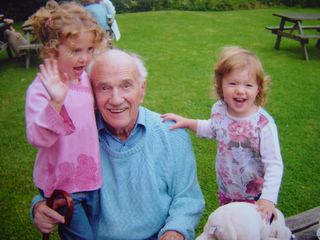

Her dad, too, a man of ritual all his life, grew more so as he grew older. He decorated his house every Christmas, put up a tree as long as he lived in his own house, across a courtyard from Granny's brother. Granny remembers with fondness and irritation both, the tone of utter tragedy in which he told her one October - he was 91 or so - 'it really is FRIGHTFUL. There are no berries on the holly this year. What

are we going to do at Christmas?'

As for his daily rituals. Granny's school mornings were defined before breakfast by the rhythmic squawk that came from the bathroom where her father was stropping his razor before shaving. And after it by the sight of him advancing on the lavatory clutching his Times, for the daily evacuation of his bowels. Interrupt him never: DON'T DARE. Dad's daily shit was sancrosanct. (And not to be called a 'shit' either in his hearing, if you valued your skin; the word 'fart' was out of order too. Granny is not quite sure how dad did refer to his excretions. She can't imagine him using the term she was told to use for hers 'big jobs ' -as opposed to 'little jobs; or 'spending a penny.' This was long before the use of 'pooh.' )

It is said that Germans are obsessed with their hearts, the French with their livers and Englishman with their bowels. If Dad was an example this is right. Not just Dad either. The historian AJP Taylor claimed that the direction of the First World War was adversely affected by Lloyd George's insistance on holding his War Cabinet first thing in the morning. The similar morning rituals of Lord Robertson's Chief of Staff thus sabotaged, he was not only famously tetchy but also desperate to hurry the proceedings on. (Lloyd George, as a Welshman obviously had no such problems. But then he wasn't trained by a nanny.)

Another thing that turned to ritual for Granny's dad, initially because of the war, was his garden. It's something else Granny finds familiar here - she walks to the local shop serenaded by chickens - at one point by a bored goat popping its head out of a stone enclosure and bleating at her indignantly. In gardens all round potatoes are coming up, rows of onions, leeks, peas, potatoes, cabbages; the small raised mounds in which each sweet potato is planted are sprouting leaves. Just so, give or take the lack of sweet potatoes, the kitchen garden of Granny's youth, in which her father endlessly laboured.

For the last 20 years of his life he contented himself with a flower garden. But throughout her childhood, the familiar sight was of her father digging, weeding or feeding chickens; of her mother bent over strawberry plants or in the raspberry cage, bowl in hand, picking raspberries. The vegetables were wonderful of course. Free range, organic - noone knew o anything else. The downside was the sheer hard labour. If Granny did not rush towards self-sufficiency in the 60s like many of her contemporaries, it was because she remembered all too well the agony of chasing escaped chickens in the dark on wet winter nights; the equal agony of picking frost-covered brussel sprouts for Sunday lunch. Granny and her siblings were often recruited as forced labour,

One reason Dad could manage this of course was his relaxed work pattern. The other reason, during the war, was his being in a reserved occupation - much to his fury - not allowed to join the army and fight like all his friends. Dig for Victory he could, though. He did dig. Besides keeping chickens; and rabbits. (We were allowed to keep two pet ones only. All the rest were for the pot. He and Granny's mother dreamed of keeping a pig too, but they never quite managed that.) All this was not just to the country's advantage either. It was to his and his family's. Rural people who could and did grow their own food were a hundred times better off through the war and the austerity afterwards when rations diminished still more.

At this point Granny's family were still living in the rented house where she and her twin were born - a ravishingly beautiful early 18th century terrace house by the Green, just next to the church. If you walk down through the churchyard today you can still look over the wall and down into the garden below. There is the lawn, backed by a low moss-covered roof, which figure in many Brownie snaps of Granny and her siblings at play. There is the chestnut tree, providing their very own supply of conkers - just over the wall from the tiny grave of Granny's younger brother, who died aged one week in 1944 - another story. There, a little way down, is what used to be Dad's precious vegetable garden. In which, aged four or so, Granny perpetrated the worst - most delicious, most irresistable- crime of her childhood.

He was planting out a row of cabbage seedlings one day. After a while creeping up behind him, she pulled out one seedling just to see what it felt like - how easily - how beautifully it came into her hand. She laid it down and pulled another; then another; the ecstasy of little destructions - the delight of each easy little pull making her forget - almost but not quite - it was part of the pleasure in a queasy way, as was the sight of her Dad's bottom just ahead of her, his his earth-covered hand reaching into trug for each plant - the retribution to follow.

At the end of the row her dad straightened, turned round. Saw each seedling lying on its side. After one look at this face Granny departed rapidly, fled up the garden into the house, hid behind the sofa, pursued first by his bellows then by himself. Her dad only believed in hitting boys - it was called corporal punishment and considered altogether a good thing, even a duty of a parent. Girls were a different matter. Yet Granny does have some vague memory of a smack when he hauled her out from her hiding-place, this time. She can't be sure. The memory of that and any further punishment has been eclipsed by her memory of the guilty pleasure of what incurred it.

As for now: granny's apology for production; her dad never aspired to the chillies or the bananas that Granny is trying to coax into life. Her cabbages appropriately a different matter, she is glad to report that Mr Handsome has bowed to the inevitable and reprieved Granny's cabbage plant. Apart from anything else he's too busy re-varnishing the wood; another victory.

Oh AND the glassman cometh. AT LAST. It's all go on Granny's little island. 'Lunchtime,' urges Beloved another man of habit, not to say ritual.