A lady once lunched

Granny once heard A.S Byatt on Desert Island Discs describing the rage in her mother's eyes when she was dying. Granny's mother died angry too. She thinks that all too many in that generation did; emancipation might have beckoned their daughters, but it came too late for them.

Her mother did not even go to to university like Byatt's - though she was ten times brighter than Granny's father who went to Oxford as a matter of course. She suffered from serious asthma -something that has resurfaced in Granny's eldest granddaughter; hers is kept well at bay by what she calls her 'puffers.' No such thing as puffers in the nineteen twenties though. When Granny's mother was fourteen, the long-suffering - in a different way - aunt who brought her up was told by their doctor that another winter in England was likely to kill her niece. Taken out of school she was sent to a finishing school in Switzerland - which expelled her before long as many of her many schools did; she was a terror. Far too young for such an institution - everyone else was 17 plus - she used to creep out of its windows at night to ski with the young instructors. She also freaked out the more innocent teachers by putting Epsom Salts in their chamber pots - causing them much alarm when they took a pee. (Alas, readers, this is not a trick your children or grandchildren or pupils can repeat in the world of the en-suite.)

Over the next few winters, therefore, the aunt herself had to traipse Granny's ma round Switzerland and Italy in order to keep her alive. In consequence, apart from speaking French, German and Italian pretty well, she was deeply uneducated. It didn't occur to anyone, least of all her, to worry about it She was only a girl after all. (This was an attitude that persisted into Granny's childhood; but for the war she and her sisters wouldn't have been sent to school, but educated, or rather uneducated, by a governess along with other nice girls of their background.) Education only a means of getting a job, women didn't need jobs - they expected their husbands to keep them. The husbands, of course, expected it too. Though granny's ma had a job she adored - in an interior decorators - her dad insisted she gave it up on her marriage to him. 'No wife of mine is going to have to work' he said - a statement all the more ironic given how much she did have to work later; even though that - housework - was not considered as such because unpaid. For the time being though, through the last six years of the 30's, she was one of that still not wholly vanished breed 'a lady who lunched.'

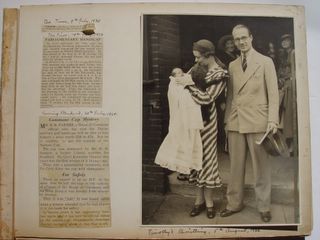

A well-lunched lady wearing a dead animal and clutching a live baby; her very first. (Spot which is which.)

This in itself was far from bad; she read voraciously, had many friends, went to the theatre, to exhibitions. She didn't have to lift a finger round the house; even a Civil Servant like Granny's father could afford a maid - as well as a daily or two, and, after the first baby arrived a nanny and nursery maid. Hard to imagine that at the time even such a household was barely considered adequate. 'If you have only one maid,' enquired Granny's grandfather, 'If you have only one maid, who will answer the door on her day out?' It was like that then for people like them, in those days of what were to Granny throughout her childhood that fabled, unreal time of 'before the war'. Which was to war-time kids like her - and to her mother, who described it often, longingly -truly another country.

She described fairy-tale fruits - bananas - oranges - grapefruit! - nowhere seen by Granny except in greengrocers' posters - as many sweets as you could eat, cream butter, toys of all kinds, your own cas even. (A car stood on chocks without its wheels in Granny's father's garage. But till Granny was seven or so the only car she ever travelled in belonged to the local taxi-drivers; the Messrs Jenner - one fat, one thin; one sour, one jolly.) Most marvellous of all - or so it seemed to her - there were glass balls, her mother said, with figures in them, in which snow began swirling if they were turned upside down. And even more amazing, there were shells from Japan that opened up in water and sprouted flowers. (Such things reappeared, or course, during the fifties. The glass balls were plastic; the flowers all paper. It wasn't till much later that it occurred to Granny that what was now all around her, commonplace enough, was exactly what she'd used to think of as beyond belief. The wonder days - by then she didn't call them that- of 'before the war' had sneaked back.)

When the war came of course, that was the wonder, the fabulous time, for younger unmarried women. The war liberated them. 'Lock up your daughters' was no longer an option for the sternest of parents. Summoned by the war machine to do their duty, unmarried daughters escaped all family shackles, lived away from home, many for the first time, had responsible jobs, affairs; generally made whoopee. Those like granny's mother, already married with young children, did not. Their servants disappeared, one by one, called-up to do much more important things than enabling ladies to lunch. Granny's mother was lucky in one way - she had an aged nanny passed on by her sister-in-law, who helped her with Granny and her sister (fragile infant twins who could not be left for a minute, she needed help with them and their elder brother more than most; to keep the twins alive not least.) Apart from that she and those like her were on their own; catapulted into being what most other women have always had had to be - fulltime house-drudges. With no relief.

So what you might say? Yes - but the women who'd always done it had at least been brought up to it. Middle-class women like my mother who had never so much as boiled an egg started from scratch in the most difficult of circumstances. Food rationed, not to say scarce, they often had to queue for it for hours - there was no meat, not even cheese left for very first meal Granny' mother cooked; a vegetable pie; it took her all morning and left her in tears. Whether the pie was edible, granny does not know.

She had no mechanical aids like food mixers to help her or any other kind of household aids, apart from an ancient, very temperamental, Hoover. (Middle-class American women, many more of them housewives, screamed for and got such aids long before English women did, who had skivvies to do the work.) Like many others she also had to do battle with a recalcitrant kitchen range which had to be relit every morning - fuel was rationed along with everything else. There were no detergents, bleach existed, but not much else, except waxy soap. All this on top of childcare. (One of Granny's mother's friends who had four children under five applied to get some help. When asked by the officer she was appealing to 'What do you do in your spare time Mrs B..?' she drew herself up. 'If I have any spare time I spent it in going to the lavatory.' She did not get her help.) On top of that, where Granny's family lived, just south of London the airraid warnings kept everyone awake half of many nights. The bombers usually passed over their head en route to the city. Sometimes, if there were bombs left over they ditched them locally. Not far away a children's home was hit and many killed. Twice during the war when things got especially bad Granny's dad moved his family to the north. But not for long.

Granny was too young to be scared by this - being hauled out of bed in the middle of the night to be fed fish-paste sandwiches while crouching under the stairs seemed an adventure to her. It's unlikely it seemed like an adventure to her exhausted and frightened mother. In her case too, the whole thing was compounded by a fierce perfectionism which meant the house had to be run as well as it was when there were servants. (No dust on top of anything, no matter how high up. Granny does not to dust the unreachable top of things; or rarely.) Nor could she let herself be seen as any different from her mostly working-class neighbours. If they could scrub their doorsteps every morning, so could she; all four of them. Their rented house, next to the church on a village green was an old coaching inn dating from the early eighteenth century, and had four steps up to the front door. It also had no doors that fitted, floorboards which gaped and no heating. Des Res that it might be thought now, the family fled to a nice thirties pad with heating and an Aga at the first possible opportunity.

Life got easier altogether after the war, despite increased rationing, fuel and petrol shortages. And Granny's mother was luckier than many in having such an adoring husband who believed in helping with the washing-up and breakfast cooking - if not with cleaning or changing nappies, that remained women's work. Desperate to help her out in all ways possible, he also brought her the first washing-machine on the market - he could ill-afford it, the value of civil service salaries had plummeted by then - but he bought it, just the same. As he insisted too she had help from a series of dailies, and up till the arrival of the washing-machine that she used a laundry for the household linen. That machine though did her no favours; not only did it flood from time to time and spin with such noise and frenzy that even bolted down it made the whole house shake, it did not, unlike laundries, iron the sheets. Go to bed in unironed linen?Unthinkable! To her, if not to Granny - who has never ironed a sheet in her life except for guests. Get real! (And she likes cotton ones. Even if hers are always crumpled.)

And still, no matter what, no matter how things eased for her, she kept on driving herself non-stop. There was always something more she felt to be done - and something she usually hated; she even hated cooking, good at it as she was. What she never had a chance to do was explore what she could have done, given the chance. Granny never got the chance to discuss with her mother what she really felt when her daughter - granny - went to Oxford. But to judge by her angry dying, Granny cannot imagine she felt well done by. What had she got out of life? Housework. With or without a frilly apron. No wonder she was angry.

If you want to know about the other women, the ones took the drudgery for granted, read Margaret Forster's Hidden Lives about her mother and grandmother. It doesn't undermine what Granny has said about her mother. Of course, once the middle-classes faced the drudgery they too clamoured so loud that the machines arrived at last. As for those scrubbed white steps: Granny's mother's might have been one kind of badge - 'look I'm not too proud to be one of you' theirs were more badges of survival. 'We may be poor but we have our pride. We do not live in the gutter.' Granny's dirty doorsteps may shout 'I have a life, I have other things to do.' But she'd better not, she thinks, laugh at those scrubbed steps, let alone despise them. What she really has to be she is - is grateful.

0 Old comments:

<< Home