Geometry

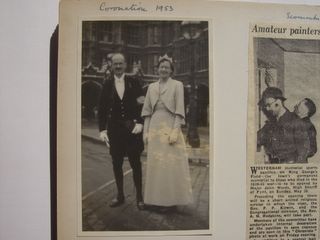

No: you are not seeing things. Granny's dad IS wearing kneebreeches and that IS a sword by his side. (Granny doubts if he had a clue how to use it.) Granny's mother IS wearing a tiara. Why? AHA. In this post - till the next maybe - Granny will not even reveal the date - it might give things away. All she will tell you is that his very much less formal attire that can be glimpsed in the fragment of photo alongside had been donned for painting scenery for the local amateur dramatic society. For the rest: AHA again. WAIT AND SEE.

Attic Woman aka the first Mrs R , latches on to words sometimes and then brings them up again and again. On Granny’s visit to her yesterday she said ‘It’s a triangle.’ She kept on saying it in one context or another, making clear that what she meant was the three of them, the first and second Mrs R and their Beloved. She seemed alright about it. 'I don't mind,' she said, Granny told her the story of her headmistress from the last post. Mrs R laughed furiously and then said ‘triangle’ again. And she and Granny held hands for a bit until the sun went in and it was time for her to be wheeled home.

Emotional triangles; yes. Granny has experienced one or two, who hasn't. Two women, one man. Two men, one woman. Not till she was an adult though – sometimes wishing she wasn’t - these are always uncomfortable and often painful situations. ‘There were always three in our marriage.’ Guess who said THAT’ Or more or less; granny is not going to chase up the original. But she imagines such triangles can be as uncomfortable and painful when polygamy is permitted rather than implicit. Her parents were, contrariwise, fiercely monogamous. When her dad remarried after her mother’s death, it stayed that way. Weeping after Granny’s stepmother’s death he said he felt bad about having stayed more devoted to his first wife. But he was a much better husband to his second wife than her first had been. She loved him dearly, he loved her too in his way and they spent twenty happy years together. Her death devastated him.

At his 75th birthday party – stepmother was too far up the table to hear, the naughty doctor’s wife leaned across to a startled Granny and said ‘I always felt sorry for you children. Your parents were so ridiculously over in love.’

This was the first time it had occurred to Granny that her parents’ mutual adoration could have been a problem. The moment she thought about it though, she began to understand what the doctor’s wife had meant.

In one sense her parents’ devotion was beautiful to be around and she’s still grateful for it. One of her friends – daughter of a far from devoted couple – claimed never to have forgotten the morning she and Granny came down to breakfast and innocently ate the bowl of wild strawberries Granny’s dad had picked especially for his wife; the fury that followed. (As the same friend has also not forgotten the time she was offered a drink and asked for whisky. Granny’s dad frowned at this – but because she was a visitor complied. Not so when Granny did likewise. Shouting ‘No daughter of mine’ etc, he handed over a glass of sherry. Young women it seemed – even older ones like Granny’s mother – drank sherry; or at the very most pink gin. Whisky was for men. Or grandmothers. Only later did Granny learn that her grandmother, his mother, kept a flask of whisky in her handbag and added goodly drams to her milkless cuppas.)

The doctor's wife comment did, however, make Granny realise the extent to which none of her parent’s four children existed in their own right. They were more an extension of the great love between them – an attempt by each of them to make up to the other for their own damaged childhoods. Granny and her siblings lived on their behalf the happily childish lives not given them: protected from the world the way they weren’t, despite a mutually abiding innocence.

The fifties were a time, anyway, when many middle-class adults tried desperately to put the horrors of the war behind the themselves and still more their young. Whispers of the worst horrors – Auschwitz, Belsen, Nagasaki - crept in; but still middle-class childhood was as enclosed as a hen-run, with anodyne children’s books to match. Even the war memoirs and stories that filled their houses like most and were read avidly by Granny were as remote as fairy-tales; gave her nightmares for a day or two, then vanished into the never-really-was, or at least could- never - happen-again. Much like the Dennis Wheatley stories of devil worship which she devoured (secretly) at the same time. She and her siblings remained wrapped in deep, terrifying innocence, even after they came across – as Granny did - such headlines as ‘H-Bomb exploded’ in the school common-room copy of the Times. Though she never felt wholly easy therefter, the innocence lived on.

It was pure Enid Blyton– there they were roaming freely across the countryside during the holidays just like the Famous Five - complete with dog if not the lurking crooks all ready to be foiled. In termtime – after the age of twelve for the girls – eight for their more unfortunate brother -they departed to boarding-school, their versions of St Clare's or Malory Towers. (Better than the descendents of Tom Brown's Rugby as suffered by the boys, for sure.) This greatly grieved Granny’s mother. She hated it every time - confessed later that she cried for two days. But because it was good for her children - she thought – she accepted it. Even despite the heart-breaking letters that arrived from her eight-year old son when he first went away. ‘I am homsick and lonly. Let me com home.’

But he had to learn to be an Englishman, she knew - Granny’s dad believed it so she had to -away from the softening influence of his mother. The theory in general was that children went to boarding-school to learn how to be independent. But actually all they did was learn how to survive in boarding-school. Not a good training for real life, if sometimes enjoyable at the time. (Granny’s dad taken in his nineties to watch his old school play another one at cricket reported with pride. ‘We won.’ Even though by now the school in question contained as little of him and what he’d experienced in it as his endless regenerating – and by now withering away - skin and flesh and bone contained of his thirteen to eighteen year old self. Very touching but sad. So you see. )

When Granny and her siblings went their own ways, still more when their lives took turns their parents found difficult to encompass, it was as if they were losing parts of themselves. Granny’s nurse sister said of them on the telephone from Australia only yesterday; ‘They were both so needy.’ Which is one way of putting it. In the version Granny arrived at. aged 22 or so, her very different, madly in love parents were like orphans in a storm, clinging together for comfort. She was observing at the time the way her parents confronted together her mother’s final illness. It was, you could say, ‘heart-warming’ ‘courageous’ etc etc. ‘How brave your parents were..’ she was always hearing. And so they were; in their way. But what it taught her – if this sounds cruel – forgive her –her sisters pretty much took the same lesson – was how NOT to do it. Confronting death is done better as a grown-up. Something the medical system itself discouraged at the time. Granny’s parents were not alone.

What orphaned her parents both - their mini, very English, very middle-class version of the history of the twentieth century she will explain – or try to – in the next post.

Labels: family stories

0 Old comments:

<< Home